(2: 安徽省高校生物环境与生态安全省级重点实验室, 芜湖 241000)

(3: 安徽师范大学图书馆, 芜湖 241000)

(2: Key Laboratory of Biotic Environment and Ecological Safety in Anhui Province, Wuhu 241000, P. R. China)

(3: Library of Anhui Normal University, Wuhu 241000, P. R. China)

表型是生物性状的外在表现,是由基因型与环境条件共同作用的结果,即使是同一基因型生物体在受到环境的差异影响时也会形成不同表型性状,这就是生物的“表型可塑性”(Phenotypic plasticity).生物的表型可塑性可以体现在形态、行为、生理和生活史特征等方面,它是生物有机体对环境变化的一种适应结果[1].轮虫是水生态系统中浮游动物类群的重要组成部分,因其繁殖速率快、世代时间短以及对环境因子变化敏感,表现出较强的形态可塑性,尤其是臂尾属轮虫(Brachionus)[2]和龟甲属轮虫(Keratella)[3].研究表明,轮虫的形态特征受到一系列外源性因素(如温度、捕食者和食物组分等)和内源性因素(如隐种和品系等)的影响[2-6],而有关环境污染物对轮虫形态可塑性的影响尤为引人关注[7].

近年来,全球变暖加剧了富营养化水体中蓝藻水华暴发,并伴随着大量有毒物质的产生,其中铜绿微囊藻(Microcystis aeruginosa)是主要优势藻种,其产生的微囊藻毒素(Microcystins, MCs)是污染水体中分布广、浓度高及毒性强的肝毒素类环境污染物[8-9].在80多种微囊藻毒素中,微囊藻毒素-LR(MC-LR)是毒性最强的一种,其可引起家禽、家畜及野生动物死亡[10],对水生生物的生长、繁殖和生理代谢等生命活动具有严重的毒害作用,甚至能够通过食物链间接危害人体健康[11-13].随着大量水华蓝藻的迅速死亡,自然水体中微囊藻毒素浓度从痕量可达到1.8 mg/L,甚至更高[14].因此,有关微囊藻毒素的毒理学效应已引起广泛关注.浮游动物轮虫是检测环境污染风险的理想模式生物之一;已有研究表明,蓝藻毒素(尤其是微囊藻毒素)对浮游动物的生长和繁殖具有长期慢性毒害作用,并可能导致牧食性浮游动物的快速死亡[15-17].然而,目前国内外尚未开展直接以纯化的微囊藻毒素对轮虫形态特征的影响研究.

温度可以调节浮游动物的代谢速率和活动水平,进而影响其生理生态和表型特征[18]. Nogrady等[19]研究发现,温度可诱导轮虫的棘刺长度发生变化;另有研究表明,低温可促使轮虫后棘刺的产生或延长[20-23];Kiełbasa等[24]研究发现,温度、食物种类及其交互作用可显著影响轮虫的形态学特征.此外,高温可增加水华的发生频率,并加剧藻毒素对有机体的毒性作用[25-26],因而温度是浮游动物对有毒蓝藻作出响应调节时的关键影响因子[27-28].迄今,有关温度和微囊藻毒素对轮虫形态特征的交互作用却未见报道.

在连续变化的环境梯度下,轮虫的形态学特征不仅受到外源性因素的影响,还受到诸如隐种(cryptic species)和地理品系(strain)等内源性因素的制约[29-31].近期的分子系统学研究表明,那些在较大地理尺度上分布的轮虫广布种存在多个遗传谱系或隐种[32],所谓的广布种事实上可能是隐种复合体,包括螺形龟甲轮虫(K. cochlearis)[33]、褶皱臂尾轮虫(B. plicatilis)[34]和萼花臂尾轮虫(B. calyciflorus)[35]等.分布于不同地理区域中的轮虫在经历了各种环境条件的长期驯化和自然选择后,往往适应于各自所处的生态位,并在形态和生态特征等方面表现出显著差异.越来越多的研究表明,不同品系轮虫在个体大小和卵体积等特征上具有显著差异[36-39],各品系轮虫间的表型可塑性能力大小各异.因此,进一步探究不同隐种或品系轮虫对温度和微囊藻毒素的响应机制显得尤为重要.

本实验采用Phmias 2008显微拍照及测量技术,研究温度和微囊藻毒素MC-LR对采自不同地域的萼花臂尾轮虫形态特征的影响,旨在为评估富营养水体中污染物的生态风险积累科学数据.

1 材料与方法 1.1 轮虫的采集与培养实验用萼花臂尾轮虫分别采自于4个不同气候区域的静水水体,即云南西双版纳自治州(BN)(22°00′N, 100°47′E)、云南昆明市(KM)(25°03′N, 102°42′E)、甘肃兰州市(LZ)(36°05′N, 103°45′E)和青海西宁市(XN)(36°39′N, 101°42′E),它们分别位于我国的热带、亚热带、温带和高原气候区;采样时各采样点水体温度分别为23、20、15和12℃.

将采集的轮虫活体带回实验室置于24±1℃、自然光照条件下(光照强度约130 lx,光:暗=14 h :10 h)的恒温培养箱中进行“克隆”培养.培养液采用EPA配方[40],并采用HB-4培养基[41]培养的处于指数增长期的斜生栅藻(Scenedesmus obliquus)作为轮虫饵料,每24 h投喂一次饵料及更换一次培养液,投喂藻类密度为1.0×106 cells/ml.培养时间在1个月以上.当各克隆轮虫达较高密度(200~300只/ml)时,将各克隆中的部分轮虫用培养液过滤冲洗,并饥饿24 h后用70 %酒精固定保存,用于后续的轮虫进化种的甄别.最终收集的轮虫克隆91个,其中西双版纳24个、昆明31个、兰州14个和西宁22个.

1.2 轮虫进化种的鉴别使用WizardTM基因组DNA纯化试剂盒提取轮虫DNA.具体步骤如下:将各轮虫克隆从-20℃冰箱中取出,梯度融化;12000转/min离心5 min,弃去上清液;加入30 μl预冷的核裂解液,56℃水浴1 h;室温冷却5 min,加入10 μl预冷的蛋白沉淀液,剧烈震荡10 s;4℃放置2 min,18℃、15000转/min离心10 min;吸取上清液至新的离心管中,加入等量异丙醇和2 μl(20 mg/ml)糖原,4℃沉淀30 min;15000转/min离心10 min,弃上清,加入100 μl 70 %乙醇,15000转/min离心5 min;弃上清,用70 %乙醇重复洗涤一次;待沉淀完全干燥后,加入30 μl无菌水溶解,-20℃保存备用.

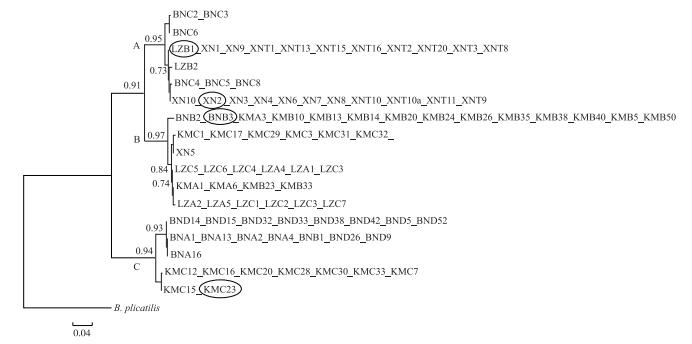

参照Xiang等[42]方法进行线粒体细胞色素c氧化酶亚基I基因(COI)的PCR扩增、测序并提交GenBank,序列登录号:昆明(KT161884~KT161914)、西双版纳(KJ862219~KJ862221、KJ862225~KJ862245)、兰州(MG323328~MG323341)和西宁(MG323384~MG323405).运用PhyML基于最大似然法(Maximum Likelihood)进行系统发育树的构建[43];两种DNA分类方法被用于萼花臂尾轮虫的进化种甄别,分别是自动条形码查询系统(Automatic Barcode Gap Discovery,ABGD)[44]和Yule溯祖模型(Generalised Mixed Yule Coalescent,GMYC)[45].当种内最大遗传距离小于种间最小遗传距离时即形成DNA条形码间隙,这是利用DNA条形码技术进行物种鉴定的基础. ABGD方法(http://wwwabi.snv.jussieu.fr/public/abgd/abgdweb.html)是基于遗传距离在种内差异先验值P区间(0.001~0.100)对样本进行划分,划分在同一组的样本被认定为是一个种. Yule溯祖模型认为在一颗超度量树上描述物种形成事件和溯祖事件,这2个事件的节点就是物种形成的界限.基于91条序列的17个单倍型,在r8s软件采用平截牛顿(truncated Newton,TN)算法和罚似然(penalized likelihood,PL)准则建立超度量树,并运用gmyc.pkg.0.9.6 R语言脚本得到聚类结果[46].

1.3 轮虫的MC-LR胁迫实验实验用微囊藻毒素MC-LR(纯度95 %)购自于依普瑞斯科技有限公司(北京),由台湾藻研有限公司(Taiwan Algal Science Inc.)生产的MC-LR(Microcystin-LR, MCYL1GAM004)分装所得.根据微囊藻毒素在全球自然水体中的浓度,本研究将微囊藻毒素浓度设置为2.0、4.0和6.0 μg/ml.实验前,用蒸馏水配制50 mg/L的MC-LR母液,于4℃冰箱中备用;实验时用EPA培养基将其逐步稀释成所需浓度的测试液;母液每3天配制一次.

根据进化种甄别分析,从现存的3个进化种中选择了4个品系(西双版纳BNB3、昆明KMC23、兰州LZB1和西宁XN2)用于后期的生态学实验.实验前,将4个品系的萼花臂尾轮虫置于不同温度的光照培养箱中(光照强度约130 lx,光:暗=14 h :10 h),采用1.0×106 cells/ml斜生栅藻为饵料对其进行为期14 d的预培养.根据4个气候带的温度特征以及采样时的水温,本研究中温度梯度设置为4组,即16、20、24和28℃.

每个品系轮虫均设置16个实验组(4个温度×3个MC-LR浓度+4个空白对照组),每组3个重复、4个品系,共计192个实验单位.实验时,从各组预培养轮虫中分别挑取200只携非混交卵的母体,分别置于各温度下含有50 ml测试液或EPA培养液(对照组)的烧杯中,轮虫初始密度约为4 ind./ml,对其进行温度和MC-LR胁迫处理48 h.期间,每24 h抽样计数各实验组的藻密度,确保藻密度为1.0×106 cells/ml.对轮虫胁迫48 h后,从各实验组随机挑取50只幼体(龄长小于2 h)分别置于含5 ml测试液或EPA培养液(对照组)的玻璃杯中继续培养.为确保用于形态测量的轮虫处于同一发育阶段,实验每隔2~5 h观察1次,待轮虫刚产出第1枚非混交卵时,取出轮虫用蒸馏水小心清洗后,再用4 %甲醛溶液进行固定,用于形态测量.

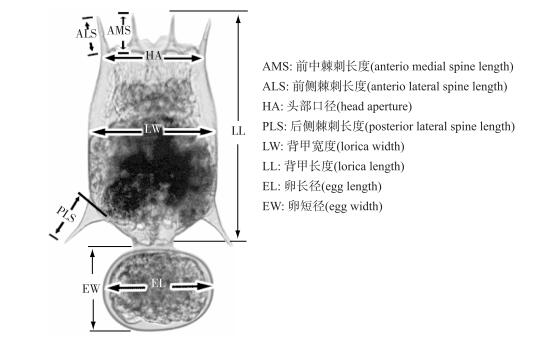

1.4 轮虫的形态测量本实验采用Phmias 2008显微装置和图像采集系统对各克隆轮虫进行拍照测量(各处理组样本量均为30个).根据萼花臂尾轮虫的形态学特征,本实验根据Fu等[47]和Ciros-Pérez等[48]的方法,设置了轮虫的8个形态参数,分别是:(A)前中棘刺长度;(B)前侧棘刺长度;(C)头部口径;(D)后侧棘刺长度;(E)背甲宽度;(F)背甲长度;(G)卵长径和(H)卵短径(图 1).

|

图 1 萼花臂尾轮虫形态测量指标 Fig.1 Brachionus calyciflorus showing the body measurements analyzed |

轮虫的个体大小(body size, BS)和卵体积(egg size, ES)的计算公式如下:

| $ BS{\rm{ = }}\frac{{{a^2} \cdot b}}{5} $ | (1) |

| $ ES = \frac{{\pi \left( {{m^2} \cdot n + n \cdot {m^2}} \right)}}{{12}} $ | (2) |

式中, a和b分别为背甲长度和背甲宽度[49],m和n分别为卵长径和卵短径[50].

1.5 数据的统计分析采用SPSS 19.0软件对实验数据进行统计分析,对所得数据作正态性检验(Kolmogorov-Smirnov)后,对符合正态分布的各组数据进行了方差分析和多重比较(SNK-q检验),以检验温度、MC-LR及其交互作用对4个品系轮虫形态特征影响的显著性.此外,采用单因素方差分析(One-way ANOVA)检验了未经MC-LR胁迫的轮虫形态学参数对温度胁迫响应的差异显著性,以及单一因素温度和MC-LR分别对兰州LZB1品系轮虫形态参数的影响.

2 结果 2.1 萼花臂尾轮虫的进化种组成通过条形码间隙分析,萼花臂尾轮虫17个单倍型序列集在遗传距离0.04~0.07范围形成明显的DNA条形码间隙.根据ABGD算法,在先验种内遗传距离(prior intraspecific divergence)P < 0.0215范围内形成相对稳定的初始分组(initial partition),分为3组.根据ABGD基于稳定的初始分组可以将序列分配到候选物种中的原理,可推测萼花臂尾轮虫由3个进化种组成.基于GMYC模型得到的结果也将该数据集划分为3个进化种.基于最大似然法构建的系统发育树见图 2.系统树中3个进化枝(A、B和C)间遗传分化水平高,支系间序列差异百分比为A—B(7.5 % ~8.6 %)、A—C(12.8 % ~13.8 %)和B—C(12.8 % ~14.8 %).因此,本研究从3个进化种中选择了4个品系(A进化种的LZB1品系和XN2品系,B进化种的BNB3品系,C进化种的KMC23品系)用于后续的生态学实验.

|

图 2 基于COI基因序列构建的萼花臂尾轮虫ML系统发生树 Fig.2 The ML phylogenetic tree of B. calyciflorus based on the COI gene sequences |

双因素方差分析结果显示,温度对4个品系萼花臂尾轮虫的10个形态学参数均有极显著影响(P < 0.001);MC-LR仅对LZB1品系轮虫的所有形态学指标影响显著,MC-LR对其他3个品系轮虫的头部口径也具有显著影响,但对其他形态学参数的影响在各品系间具有不一致性;温度与MC-LR的交互作用仅对LZB1品系轮虫的所有形态学参数产生显著影响(表 1).

| 表 1 温度(T)、MC-LR(M)及两者交互作用(T×M)对4个品系萼花臂尾轮虫形态学参数的影响(F值) Tab.1 Effects of temperature (T), MC-LR (M) and their interaction (T×M) on the morphometric parameters of the four B. calyciflorus strains (F value) |

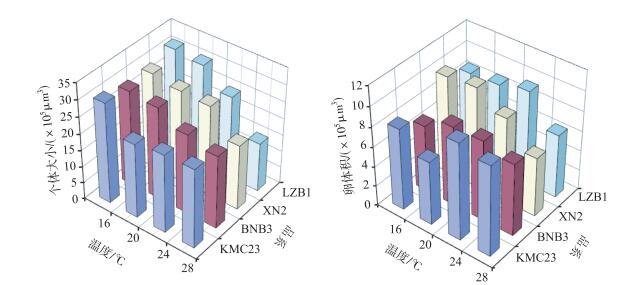

单因素方差分析结果表明,除了BNB3品系的卵长径和LZB1品系的卵短径之外,4个品系的轮虫形态学参数均受到温度的显著影响;多重比较结果显示,随着温度的升高,各品系轮虫的大部分形态学参数呈减小趋势(表 2,图 3).

| 表 2 温度对4个品系萼花臂尾轮虫形态学参数的影响* Tab.2 The effects of temperature on the morphological indexes in four strains of B. calyciflorus |

|

图 3 温度对4个品系萼花臂尾轮虫个体大小和卵体积的影响 Fig.3 The effects of temperature on the body size and egg size in four strains of B. calyciflorus |

温度对轮虫KMC23形态学参数影响的比较结果表明,在16℃下,除了轮虫卵特征参数外,KMC23品系的其他形态学参数均最大,而在20℃下,除背甲长度之外,其他形态参数均呈现最小. KMC23品系的卵长径和卵体积在20℃最小,在24℃下最大,但该最大值与在16和28℃下的参数值之间无明显差异.就个体大小而言,在16℃低温胁迫下KMC23品系轮虫的个体增大,而其他温度处理组与24℃对照组间无显著差异(表 2,图 3).

单因素方差分析表明,除卵短径外,BNB3品系轮虫的其他形态学参数均在16℃下最大,而各类型棘刺长度在24℃培养温度下最小;背甲长度、背甲宽度和个体大小随着培养温度的升高而减小.轮虫的卵体积在低温16℃和高温28℃胁迫下明显减小,且在16℃下最小(表 2,图 3).

温度对XN2品系轮虫的形态学参数的影响结果表明,在28℃下,XN2品系轮虫的所有10个形态学参数值均最小.相对于24℃,经16和20℃低温胁迫后的XN2品系轮虫的8个形态学参数均增大,即使有些不具有显著的统计学意义(表 2,图 3).

就LZB1轮虫的形态学参数而言,以24℃为对照组,经16和20℃低温胁迫后的轮虫形态学参数(除轮虫卵特征参数外)均表现为增大;在28℃下LZB1品系轮虫的所有10个形态学参数均最小,这与XN2品系轮虫对高温胁迫的响应情况相同(表 2,图 3).

2.2.2 不同温度下4个品系萼花臂尾轮虫的形态特征差异对各品系间轮虫形态学参数进行单因素方差分析,结果表明,在高温下(28℃)的昆明品系和西双版纳品系形态学参数显著大于兰州品系和西宁品系;除轮虫卵特征参数外,西双版纳品系和昆明品系间未见显著差异,或者西双版纳品系略大于昆明品系.在24℃下,西宁品系的大多数形态学参数显著增大,少数形态学特征在各品系间无显著差异. 20℃实验条件下,昆明品系的形态学参数最小,而西宁品系的大部分参数最大,西双版纳品系和兰州品系间无显著差异.最低实验温度下(16℃),除轮虫卵特征参数外,各品系间轮虫形态学参数基本上没有显著差异.

综合分析发现,在低温16℃下,除轮虫卵特征参数外,4个品系轮虫的其他形态学参数总体比其他温度下有增大趋势,且各品系间参数基本上没有显著差异.在20℃下,无论是温度间比较还是品系间比较,昆明品系轮虫KMC23的大多数形态参数均最小,而此时西宁品系的轮虫最大.在24℃下,相对于其他温度而言,各品系轮虫的形态学参数均处于中等大小,而就品系间比较来说,西宁品系的大多数形态学参数显著增大.在28℃下,LZB1和XN2两品系轮虫的所有10个形态学参数在各温度中均最小,而相较于其他两个品系轮虫,其形态参数和个体大小总体呈显著性下降趋势.

值得注意的是,4个品系轮虫的卵特征参数对温度变化的响应有所不同,KMC23和BNB3两品系轮虫的卵体积分别在20℃和16℃下显著减小,而LZB1和XN2两品系轮虫的卵体积均在28℃下明显减小,该现象可能与不同品系轮虫对环境的适应机制不同从而致使能量分配不同有关(表 2).

2.3 温度和MC-LR对LZB1品系萼花臂尾轮虫形态特征的影响基于单一因素温度或MC-LR分别对LZB1品系萼花臂尾轮虫形态特征的影响开展了单因素方差分析和多重比较,结果显示,温度和MC-LR对LZB1品系轮虫的形态学参数均具有显著性影响(表 1,表 3).

| 表 3 温度和MC-LR浓度对LZB1品系萼花臂尾轮虫形态学参数的影响 Tab.3 The effects of temperatures and MC-LR concentrations on the morphological indexes in the LZB1 strain of B. calyciflorus |

温度对LZB1品系轮虫形态学特征的单因素方差分析结果表明,相对于24℃下培养的轮虫而言,无论MC-LR浓度如何,LZB1品系轮虫的所有10个形态学参数在28℃下均显著减小(除2.0 μg/ml MC-LR下的轮虫卵短径外);而在低温(16和20℃)培养下的轮虫,除卵长径、卵短径和卵体积之外,轮虫的其他形态学参数均较对照组显著增大,其中大部分形态学参数在两低温组别间未见显著差异(表 3).

2.3.2 MC-LR对LZB1品系萼花臂尾轮虫形态特征的影响在16℃下,无论MC-LR浓度如何,LZB1品系轮虫的前中棘刺长度、后侧棘刺长度、背甲长度、背甲宽度、卵短径和个体大小在各浓度组间均无显著差异;而轮虫的头部口径、前侧棘刺长度、卵长径和卵体积则在高浓度(6.0 μg/ml)的MC-LR胁迫下显著减小(表 3,图 4).

|

图 4 4个温度下MC-LR对LZB1品系萼花臂尾轮虫个体大小和卵体积的影响 Fig.4 The effects of MC-LR on the body size and egg size in the LZB1 strain of B. calyciflorus under four temperatures |

在20℃下,除卵长径和卵体积外,高浓度(6.0 μg/ml)的MC-LR显著降低了轮虫的所有其他形态学参数;而在低浓度(2.0和4.0 μg/ml)MC-LR胁迫下,除前侧棘刺长度之外的所有轮虫形态学特征均未见显著差异(表 3).

在24℃培养温度下,以0 μg/ml MC-LR为对照组,各浓度MC-LR对LZB1品系轮虫形态学参数的单因素方差分析结果表明,LZB1品系轮虫的头部口径、前侧棘刺长度、前中棘刺长度、卵长径、卵短径和卵体积6个形态参数在2.0 μg/ml MC-LR胁迫下均显著减小(部分参数在4.0 μg/ml浓度下也显著减小),而其中前5个形态学参数在6.0 μg/ml MC-LR处理下与对照组无显著差异;除上述6个形态学参数外,轮虫的其他4个形态学特征在MC-LR各浓度组间无显著差异(表 3,图 4).

在28℃高温胁迫下,除卵短径外,LZB1品系轮虫的其他形态学参数对各浓度MC-LR的响应无显著差异(表 3).

综上所述,经高温胁迫后的LZB1品系轮虫的所有形态学参数均显著减小,且不同剂量MC-LR处理组的形态学参数较对照组无显著差异;经低温胁迫后,除轮虫卵特征参数外,轮虫其他形态学参数较24℃对照组显著增大,但总体而言,低温下低浓度的MC-LR没有显著改变LZB1品系轮虫的形态学参数,而低温下高浓度的MC-LR显著降低了轮虫的大部分形态学参数.实验结果表明,温度和MC-LR对LZB1品系轮虫的形态学参数具有显著影响.

3 讨论 3.1 温度对4个品系萼花臂尾轮虫形态学特征的影响贝格曼定律指出,在相同的环境条件下,所有恒温动物每单位体表面积所散失的热量相等[51]. Bertalanffy[52]认为贝格曼定律是动物适应环境温度变化的一种表型可塑性体现,即反映了个体大小与环境温度的关系. Atkinson[53]研究发现,超过80 %的变温动物在高温下表现出生长较快但成年个体较小的趋势,这种趋势被称为温度—大小规则(temperature-size rule,TSR).之后,又有大量研究表明,大多数动物在低温下个体较大,而在高温下呈变小趋势,这与贝格曼定律及温度—大小规则相符[54-57].有关浮游动物轮虫的表型可塑性的研究早有报道.研究表明,温度胁迫可诱导轮虫的形态学特征发生变化[3, 58],如螺形龟甲轮虫(K. cochlearis)的后棘刺与温度呈负相关性[20-22, 59-61];低温可诱导尾突臂尾轮虫(B. caudatus)的后侧棘刺的产生或延长,且轮虫的背甲长度与其前侧棘刺长度及前中棘刺长度呈正相关性[23];高温可诱导轮虫背甲长度减小,同时温度与食物种类的交互作用对轮虫的个体大小有显著影响[24].温度或食物密度等不同环境因子在诱导轮虫形态特征发生改变的同时,还可能伴随着生活史对策的变化,如Athibai等[23, 62-63]的研究.轮虫所具有的这种表型可塑性同其他生物一样,是其在进化过程中对环境温度变化的一种适应性表现,根据能量平衡原则,轮虫在生存、繁殖以及代谢消耗等各方面的能量分配始终存在一个权衡(trade-off);在低温下,轮虫通过增大体积,减小相对体表面积,从而降低代谢消耗能,达到增加自身存活率和繁殖率的目的[19, 64].

本研究中,温度对4个品系萼花臂尾轮虫的所有形态学参数均具有显著影响.低温16℃可诱导未经MC-LR胁迫的所有品系轮虫的棘刺长度和个体大小明显增加,28℃的高温胁迫可导致LZB1和XN2两品系轮虫的所有形态学参数,以及BNB3品系个体体积的显著减小.然而,轮虫卵特征参数却表现出不一致性,低温16℃胁迫显著减小了BNB3品系的卵体积,20℃显著减小了KMC23品系的卵体积,而28℃的高温致使XN2品系和LZB1品系轮虫的卵体积显著减小,可见轮虫在增大体积和降低代谢消耗能的同时,并不以牺牲自身繁殖付出为代价.此前的研究也表明,品系对轮虫休眠卵参数的影响取决于食物浓度,其中芜湖品系轮虫休眠卵参数与温度呈曲线相关,而青岛品系则未见显著相关性[65].王金霞[66]比较研究了萼花臂尾轮虫8个地理种群间的形态差异,结果显示,不同地理种群间的形态参数对温度升高的响应存在着差异,形态特征不能用于不同地理种群轮虫的准确甄别,轮虫的形态学参数与采样时的水温、采样点的年平均温度和纬度呈显著相关.可见,隐种间的差异也是造成4个轮虫克隆形态学参数对温度差异响应的内源性因素.轮虫隐种间虽然缺乏特征明显的形态学表型差异,但由于其对特定生境的长期适应,从而具有了明显的生态特化和对逆境的不同抵抗力.

水体中溶解氧浓度随温度的升高而减少[54, 67-68],而在高温低氧条件下,生物有机体或细胞可能会通过减小自身体积来降低对氧气的需求[67].已有研究证实,这种适应机制同样存在于轮虫中. Kie łbasa等[24]研究发现,轮虫的个体大小随温度的升高而减小,随溶解氧浓度的增加而增大.本研究中,4个品系轮虫对温度的响应性特征存在异同之处.其中,KMC23品系和BNB3品系分别采自亚热带的昆明和热带的西双版纳的水体中,而LZB1品系和XN2品系轮虫采自暖温带的兰州和高原气候区西宁的水体中,这两个品系轮虫对温度的响应性特征也较为相似,这也可能与两者属于同一进化种有关.因此,品系间形态特征对温度的差异性响应可能是它们对栖息地条件(尤其是温度和溶解氧)长期适应的结果.

3.2 温度和MC-LR对LZB1品系萼花臂尾轮虫形态特征的影响在自然水生态系统中,浮游动物多以浮游植物为食,同时它们又是较高营养级生物的捕食对象,因此浮游动物在淡水生态系统食物链中起着重要的枢纽作用.随着水温升高,环境中微囊藻毒素的释放量不断增加,从而导致轮虫相应地调整自身的适应方式,最大限度地提高自身的适合度.

本研究发现,低温条件下低浓度的MC-LR没有显著改变LZB1品系轮虫的形态学参数,而高浓度的MC-LR对轮虫大部分形态参数产生了显著抑制作用,这表明在低温下轮虫对环境污染物MC-LR的抵抗是一个耗能的过程,轮虫可通过减小形态学参数和节约生长能量以增加对MC-LR的耐受性.此外,有研究发现个体小的物种对污染物的敏感性弱于个体大的物种[69],即小个体生物的耐受性更高,抵抗力更强[70].在高温28℃胁迫下,LZB1品系轮虫的所有形态学参数均显著减小,但MC-LR浓度对该品系轮虫的形态学参数并未产生显著影响.本研究推测,MC-LR对轮虫形态学特征的上述影响结果可能与轮虫的生活史特征有关.已有研究发现,萼花臂尾轮虫的生殖前期和胚胎发育期均随着温度的升高而缩短,其种群内禀增长率随着温度增加而增大[63, 71-72].本研究中,由于低温下轮虫的生殖前期和胚胎发育期可能较长,从而间接地延长了高浓度的MC-LR对轮虫的胁迫时间;同时,由于MC-LR在浮游动物体内具有生物富集作用[73],进而引起MC-LR在轮虫体内的累积含量随着胁迫时间的延长而增加,最终可能导致了高浓度的MC-LR对低温下萼花臂尾轮虫的形态学特征产生显著抑制作用.反之,高温下的轮虫种群可能具有较短的生殖前期和胚胎发育期以及较高的繁殖率和种群增长率等生活史特征,从而导致MC-LR对轮虫的胁迫时间缩短,富集含量减少,这可能是MC-LR对高温下萼花臂尾轮虫形态学特征未产生显著影响的原因之一.

鉴于蓝藻水华暴发时水体中的理化和生物因子(如温度和食物)发生变化,因子间的交互作用对轮虫和微囊藻起到协同或拮抗效应,进而影响食物链中高营养级的其他生物种类.因此,深入开展两种及以上环境因子交互作用的研究将进一步揭示全球变暖、蓝藻暴发和环境变迁等对轮虫种群的影响机制[74].

4 结论基于分子系统学、群体累积培养技术和微型测量技术,本研究发现:采自西双版纳、昆明、兰州和西宁4个区域的萼花臂尾轮虫种复合体由3个进化种组成;温度对4个品系萼花臂尾轮虫的所有形态学参数均具有显著影响,其形态特征随温度的升高呈减小趋势;品系和隐种的不同是造成4个轮虫克隆形态学参数对温度差异响应的重要内源性因素;在高温胁迫下,MC-LR浓度对兰州LZB1品系轮虫的形态学参数并未产生显著影响,且低温条件下低浓度的MC-LR也未显著改变其形态学参数,但低温高浓度的MC-LR显著降低了该轮虫的大部分形态学参数.

| [1] |

West-Eberhard MJ. Developmental plasticity and evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

|

| [2] |

Saksena DN, Kulkarni N. Polymorphosis in a brachionid rotifer, Brachionus quadridentatus. Hermann from Morar channel Gwalior(India). Proceedings:Animal Sciences, 1986, 95(3): 365-369. DOI:10.1007/BF03179370 |

| [3] |

Green J. Morphological variation of Keratella cochlearis (Gosse) in Myanmar (Burma) in relation to zooplankton community structure. Hydrobiologia, 2007, 593(1): 5-12. DOI:10.1007/s10750-007-9072-7 |

| [4] |

Sanoamuang LO. The effect of temperature on morphology, life history and growth rate of Filinia terminalis (Plate) and Filinia cf. pejleri Hutchinson in culture. Freshwater Biology, 1993, 30(2): 257-267. DOI:10.1111/fwb.1993.30.issue-2 |

| [5] |

Zhang H, Brönmark C, Hansson LA. Predator ontogeny affects expression of inducible defense morphology in rotifers. Ecology, 2017, 98(10): 2499-2505. DOI:10.1002/ecy.1957 |

| [6] |

Yin XW, Jin W, Zhou YC et al. Hidden defensive morphology in rotifers:Benefits, costs, and fitness consequences. Scientific Reports, 2017, 7: 4488. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-04809-z |

| [7] |

Alvarado-Flores J, Rico-Martínez R, Adabache-Ortíz A et al. Morphological alterations in the freshwater rotifer Brachionus calyciflorus, Pallas 1766(Rotifera:Monogononta) caused by vinclozolin chronic exposure. Ecotoxicology, 2015, 24(4): 915-925. DOI:10.1007/s10646-015-1434-8 |

| [8] |

Codd GA. Cyanobacterial toxins, the perception of water quality, and the prioritization of eutrophication control. Ecological Engineering, 2000, 16(1): 51-60. DOI:10.1016/S0925-8574(00)00089-6 |

| [9] |

Frazão B, Martins R, Vasconcelos V. Are known cyanotoxins involved in the toxicity of picoplanktonic and filamentous north Atlantic marine cyanobacteria?. Marine Drugs, 2010, 8(6): 1908-1919. DOI:10.3390/md8061908 |

| [10] |

Whitton BA, Potts M. The ecology of cyanobacteria:their diversity in time and space. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2000.

|

| [11] |

Carmichael WW, Mahmood NA, Hyde EG. Natural toxins from cyanobacteria (blue-green) algae. In: Hall S, Strichartz G eds. Marine toxins: origins, structure and molecular pharmacology. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society, 1990.

|

| [12] |

Berry JP, Lind O. First evidence of "paralytic shellfish toxins" and cylindrospermopsin in a Mexican freshwater system, Lago Catemaco, and apparent bioaccumulation of the toxins in "tegogolo" snails (Pomacea patula catemacensis). Toxicon, 2010, 55(5): 930-938. DOI:10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.07.035 |

| [13] |

Barrios CA, Nandini S, Sarma SS. Effect of crude extracts of Dolichospermum planctonicum on the demography of Plationus patulus (Rotifera) and Ceriodaphnia cornuta (Cladocera). Ecotoxicology, 2015, 24(1): 85-93. DOI:10.1007/s10646-014-1358-8 |

| [14] |

Chorus I, Bartram J. Toxic cyanobacteria in water. A guide to their public health consequences, monitoring, and management. London: E & FN Spon, 1999.

|

| [15] |

Paerl HW, Rd FR, Moisander PH et al. Harmful freshwater algal blooms, with an emphasis on cyanobacteria. The Scientific World Journal, 2001(1): 76-113. |

| [16] |

Lürling M. Daphnia growth on microcystin-producing and microcystin-free Microcystis aeruginosa in different mixtures with the green alga Scenedesmus obliquus. Limnology and Oceanography, 2003, 48(6): 2214-2220. DOI:10.4319/lo.2003.48.6.2214 |

| [17] |

Zhang X, Geng H. Effect of Microcystis aeruginosa on the rotifer Brachionus calyciflorus at different temperatures. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2012, 88(1): 20-24. DOI:10.1007/s00128-011-0450-5 |

| [18] |

Claska ME, Gilbert JJ. The effect of temperature on the response of Daphnia to toxic cyanobacteria. Freshwater Biology, 1998, 39(2): 221-232. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2427.1998.00276.x |

| [19] |

Nogrady T, Wallance RL, Snell TW. Guide to the identification of the micro invertebrates of the continental waters of the world. The Hague: SPB Academic Publishing, 1993.

|

| [20] |

Bielañska-Grajner I. Influence of temperature on morphological variation in populations of Keratella cochlearis (Gosse) in Rybnik Reservoir. Hydrobiologia, 1995, 313/314(1): 139-146. DOI:10.1007/BF00025943 |

| [21] |

Diéguez M, Modenutti B, Queimalios C. Influence of abiotic and biotic factors on morphological variation of Keratella cochlearis (Gosse) in a small Andean lake. Hydrobiologia, 1998, 387/388: 289-294. |

| [22] |

Xi YL, Jin HJ, Xie P et al. Morphological variation of Keratella cochlearis (Rotatoria) in a shallow, eutrophic subtropic Chinese lake. Journal of Freshwater Ecology, 2002, 17(3): 447-454. DOI:10.1080/02705060.2002.9663919 |

| [23] |

Athibai S, Sanoamuang L. Effect of temperature on fecundity, life span and morphology of long-spined and short-spined clones of Brachionus caudatus, f. apsteini (Rotifera). International Review of Hydrobiology, 2008, 93(6): 690-699. DOI:10.1002/iroh.v93:6 |

| [24] |

Kiełbasa A, Walczyńska A, Fiałkowska E et al. Seasonal changes in the body size of two rotifer species living in activated sludge follow the temperature-size rule. Ecology and Evolution, 2014, 24(4): 4678-4689. |

| [25] |

Jang MH, Ha K, Joo GJ et al. Toxin production of cyanobacteria is increased by exposure to zooplankton. Freshwater Biology, 2003, 48(9): 1540-1550. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2427.2003.01107.x |

| [26] |

El-shehawy R, Gorokhova E, Fernández-Piñas F et al. Global warming and hepatotoxin production by cyanobacteria:what can we learn from experiments?. Water Research, 2012, 46(5): 1420-1429. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2011.11.021 |

| [27] |

Gilbert JJ. Effect of temperature on the response of planktonic rotifers to a toxic cyanobacterium. Ecology, 1996, 77(4): 1174-1180. DOI:10.2307/2265586 |

| [28] |

Montagnes D, Kimmance S, Tsounis G et al. Combined effect of temperature and food concentration on the grazing rate of the rotifer, Brachionus plicatilis. Marine Biology, 2001, 139(5): 975-979. DOI:10.1007/s002270100632 |

| [29] |

Awaiss A, Kestemont P. An investigation into the mass production of the freshwater rotifer Brachionus calyciflorus Pallas 2. Influence of temperature on the population dynamics. Aquaculture, 1992, 105(3/4): 337-334. |

| [30] |

Hu HY, Xi YL. Demographic parameters and mixis of three Brachionus angularis Gosse (Rotatoria) strains fed on different algae. Limnologica, 2008, 38(1): 56-62. DOI:10.1016/j.limno.2007.08.002 |

| [31] |

Snell TW. Rotifers as models for the biology of aging. International Review of Hydrobiology, 2014, 99(1/2): 84-95. |

| [32] |

Gómez A, Serra M, Carvalho GR et al. Speciation in ancient cryptic species complexes:evidence from the molecular phylogeny of Brachionus plicatilis (rotifera). Evolution, 2002, 56(7): 1431-1444. DOI:10.1111/evo.2002.56.issue-7 |

| [33] |

Derry AM, Hebert PDN, Prepas EE. Evolution of rotifers in saline and subsaline lakes:A molecular phylogenetic approach. Limnology and Oceanography, 2003, 48(2): 675-685. DOI:10.4319/lo.2003.48.2.0675 |

| [34] |

Ciros-Pérez J, Gómez A, Serra M. On the taxonomy of three sympatric sibling species of the Brachionus plicatilis (Rotifera) complex from Spain, with the description of B. ibericus n. sp. Journal of Plankton Research, 2001, 23(12): 1311-1328. DOI:10.1093/plankt/23.12.1311 |

| [35] |

Gilbert JJ, Walsh EJ. Brachionus calyciflorus is a species complex:Mating behavior and genetic differentiation among four geographically isolated strains. Hydrobiologia, 2005, 546(1): 257-265. DOI:10.1007/s10750-005-4205-3 |

| [36] |

Snell TW, Carrillo K. Body size variation among strains of the rotifer Brachionus plicatilis. Aquaculture, 1984, 37(4): 359-367. DOI:10.1016/0044-8486(84)90300-4 |

| [37] |

Xi YL, Liu GY, Jin HJ. Population growth, body size, and egg size of two different strains of Brachionus calyciflorus pallas (rotifer) fed different algae. Journal of Freshwater Ecology, 2002, 17(2): 185-190. DOI:10.1080/02705060.2002.9663886 |

| [38] |

Hu HY, Xi YL, Geng H. Effects of food concentration on population growth, and body and egg volume in three strains of Brachionus angularis. Zoological Research, 2002, 23(5): 384-388. [胡好远, 席贻龙, 耿红. 食物浓度对三个地理品系角突臂尾轮虫种群增长、个体大小和卵体积的影响. 动物学研究, 2002, 23(5): 384-388.] |

| [39] |

Hu HY, Xi YL, Geng H. Comparative studies on individual growth and development of three Brachionus angularis strains. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 2003, 14(4): 565-568. [胡好远, 席贻龙, 耿红. 三个品系角突臂尾轮虫生长和发育的比较研究. 应用生态学报, 2003, 14(4): 565-568.] |

| [40] |

Peltier WH, Weber CI. Methods for measuring the acute toxicity of effluents to freshwater and marine organisms, EPA/600/4-85/013. Cincinnati, Ohio: United States Environmental Protect Agency, 1985.

|

| [41] |

Li SH, Zhu H, Xia YZ et al. The mass culture of unicellular green algae. Acta Hydrobiologica Sinica, 1959, 4: 462-472. [黎尚豪, 朱蕙, 夏宜琤等. 单细胞绿藻的大量培养试验. 水生生物学集刊, 1959, 4: 462-472.] |

| [42] |

Xiang XL, Xi YL, Wen XL et al. Genetic differentiation and phylogeographical structure of the Brachionus calyciflorus complex in eastern China. Molecular Ecology, 2011, 20(14): 3027-3044. DOI:10.1111/mec.2011.20.issue-14 |

| [43] |

Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V et al. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies:Assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Systematic Biology, 2010, 59(3): 307-321. DOI:10.1093/sysbio/syq010 |

| [44] |

Puillandre N, Lambert A, Brouillet S et al. ABGD, automatic barcode gap discovery for primary species delimitation. Molecular Ecology, 2012, 21(8): 1864-1877. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05239.x |

| [45] |

Pons J, Barraclough TG, Gómez-Zurita J et al. Sequence-based species delimitation for the DNA taxonomy of undescribed insects. Systematic Biology, 2006, 55(4): 595-609. DOI:10.1080/10635150600852011 |

| [46] |

Sanderson MJ. Estimating absolute rates of molecular evolution and divergence times:a penalized likelihood approach. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 2002, 19(1): 101-109. DOI:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003974 |

| [47] |

Fu Y, Hirayama K, Natsukari Y. Morphological differences between two types of the rotifer Brachionus plicatilis O. F. Müller. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 1991, 151(1): 29-41. DOI:10.1016/0022-0981(91)90013-M |

| [48] |

Ciros-Pérez J, Gomez A, Serra M. On the taxonomy of three sympatric sibling species of the Brachionus plicatilis (Rotifera) complex from Spain, with the description of B. ibericus n. sp.. Journal of Plankton Research, 2001, 23(12): 1311-1328. DOI:10.1093/plankt/23.12.1311 |

| [49] |

Zhang ZS, Huang XF. Methods for the plankton study in freshwater. Beijing: Science Press, 1991. [章宗涉, 黄祥飞. 淡水浮游生物研究方法. 北京: 科学出版社, 1991.]

|

| [50] |

Sarma SSS, Rao TR. Effect of food level on body size and egg size in a growing population of the rotifer Brachionus patulus Muller. Archiv für Hydrobiologie, 1987, 111(2): 245-253. |

| [51] |

Bergmann C. Vber die Verhältnisse der Wärmeökonomie der Thiere zu ihrer Grösse. Gottinger Studien, 1847, 3. |

| [52] |

Bertalanffy L. Principles and theory of growth. In: Nowinski WW ed. Fundamental aspects of normal and malignant growth. New York: Elsevier, 1960.

|

| [53] |

Atkinson D. Temperature and organism size-A biological law for ectotherms?. Advances in Ecological Research, 1994, 25(6): 1-58. |

| [54] |

Atkinson D, Morley SA, Hughes RN. From cells to colonies:at what levels of body organization does the 'temperature-size rule' apply?. Evolution and Development, 2006, 8(2): 202-214. DOI:10.1111/ede.2006.8.issue-2 |

| [55] |

Walters RJ, Hassall M. The temperature-size rule in ectotherms:May a general explanation exist after all?. American Naturalist, 2006, 167(4): 510-523. |

| [56] |

Arendt JD. Size-fecundity relationships, growth trajectories, and the temperature-size rule for ectotherms. Evolution, 2011, 65(1): 43-51. DOI:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01112.x |

| [57] |

Forster J, Hirst AG. The temperature-size rule emerges from ontogenetic differences between growth and development rates. Functional Ecology, 2012, 26(2): 483-492. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2011.01958.x |

| [58] |

Lindström K, Pejler B. Experimental studies on the seasonal variation of the rotifer Keratella cochlearis (Gosse). Hydrobiologia, 1975, 46(2): 191-197. |

| [59] |

Eloranta P. Notes on the morphological variation of the rotifer species Keratella cochlearis (Gosse) s.l. in one eutrophic pond. Journal of Plankton Research, 1982, 4(2): 299-312. DOI:10.1093/plankt/4.2.299 |

| [60] |

Hillbricht-Ilkowska A. Morphological variation of Keratella cochlearis (Gosse) in Lake Biwa, Japan. Hydrobiologia, 1983, 104(1): 297-305. DOI:10.1007/BF00045981 |

| [61] |

Green J. Morphologicalvariation of Keratella cochlearis (Gosse) in a backwater of the river thames. Hydrobiologia, 2005, 546(1): 189-196. DOI:10.1007/s10750-005-4121-6 |

| [62] |

Hu HY, Xi YL, Geng H. Effects of temperature on life history strategies of three strains of Brachionus angularis Gosse. Acta Hydrobiologica Sinica, 2004, 28(3): 284-288. [胡好远, 席贻龙, 耿红. 温度对三品系角突臂尾轮虫生活史策略的影响. 水生生物学报, 2004, 28(3): 284-288.] |

| [63] |

Xiang XL, Xi YL, Zhang JY et al. Effects of temperature on survival, reproduction, and morphotype in offspring of two Brachionus calyciflorus (Rotifera) morphotypes. Journal of Freshwater Ecology, 2010, 25(1): 9-18. DOI:10.1080/02705060.2010.9664352 |

| [64] |

Yampolsky LY, Scheiner SM. Why larger offspring at lower temperatures? A demographic approach. American Naturalist, 1996, 147(1): 86-100. DOI:10.1086/285841 |

| [65] |

Liu GY, Xi YL. Morphological characteristics of resting eggs produced by different Brachionus calyciflorus strains. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 2006, 17(7): 1344-1347. [刘桂云, 席贻龙. 不同品系萼花臂尾轮虫休眠卵的形态特征. 应用生态学报, 2006, 17(7): 1344-1347.] |

| [66] |

Wang JX. Spatial variation of morphological and ecological characteristics of Brachionus calyciflorus (Rotifera) from East China[Dissertation]. Wuhu: Anhui Normal University, 2010. [王金霞. 萼花臂尾轮虫形态和生态特征在中国东部的空间分化[学位论文]. 芜湖: 安徽师范大学, 2010. ]

|

| [67] |

Woods HA. Egg-mass size and cellsize:Effects of temperature on oxygen distribution. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 1999, 39(2): 244-252. |

| [68] |

Harrison JF, Cease AJ, Vandenbrooks JM et al. Caterpillars selected for large body size and short development time are more susceptible to oxygen-related stress. Ecology and Evolution, 2013, 3(5): 1305-1316. DOI:10.1002/ece3.2013.3.issue-5 |

| [69] |

Hanazato T. Pesticide effects on freshwater zooplankton:an ecological perspective. Environmental Pollution, 2001, 112(1): 1-10. DOI:10.1016/S0269-7491(00)00110-X |

| [70] |

Vinebrooke R, Cottingham K, Norberg J et al. Impacts of multiple stressors on biodiversity and ecosystem functioning:the role of species co-tolerance. Oikos, 2004, 104(3): 451-457. DOI:10.1111/oik.2004.104.issue-3 |

| [71] |

Wang XL, Xiang XL, Xia MN et al. Differences in life history characteristics between two sibling species in Brachionus calyciflorus complex from tropical shallow lakes. Annales de Limnologie-International Journal of Limnology, 2014, 50(4): 289-298. DOI:10.1051/limn/2014024 |

| [72] |

Xiang XL, Chen YY, Han Y et al. Comparative studies on the life history characteristics of two Brachionus calyciflorus strains belonging to the same cryptic species. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology, 2016, 69: 138-144. DOI:10.1016/j.bse.2016.09.003 |

| [73] |

Ferrãofilho ADS, Kozlowskysuzuki B. Cyanotoxins:bioaccumulation and effects on aquatic animals. Marine Drugs, 2011, 9(12): 2729-2772. DOI:10.3390/md9122729 |

| [74] |

Liang Y, Ouyang K, Xu HH et al. Effects of Microcystis aeruginosa on the life-tableparameters and phenotypic traits of rotifers. Acta Hydrobiologica Sinica, 2017, 41(6): 1362-1368. [梁叶, 欧阳凯, 许欢欢等. 铜绿微囊藻对轮虫生命表参数和表型特征的影响. 水生生物学报, 2017, 41(6): 1362-1368. DOI:10.7541/2017.168] |

2018, Vol. 30

2018, Vol. 30