(2: 法国国家科学研究中心(雷恩第一大学), 雷恩 35000)

(2: CNRS, Univ Rennes, Géosciences Rennes, UMR 6118, Rennes 35000, France)

拦河筑坝建库后产生的拦蓄效应导致入库河流水动力减缓,这不仅改变了天然河流的水文特性,而且直接影响了水库内沉积物有机质(OM)的时空分布、埋藏及输送[1-2]。由于河道型水库具有河流与水库的双重特性,其沉积物OM的组成复杂、来源多样,全面了解河道型水库沉积物OM的动态变化仍具挑战性。以往的研究显示,水库表层沉积物OM的来源主要受到陆源和内源的双重影响[3-5],且通常为自然源(如浮游植物、沉水植物、藻类和草本植物)和人为源贡献的复杂组合。因此,追踪水库沉积物中的OM来源,有助于理解有机碳的保存过程,对于逆转水环境变化和管理水质具有重要意义,并为水库的管理和保护提供科学依据。

迄今为止,多种研究工具均已被广泛用于表征OM的特征与来源,包括稳定碳同位素、分子生物标志物和光谱指数等。其中,稳定碳同位素单一技术能够通过稳定同位素比率区分异地和本地来源[6],但在应用过程中由于OM迁移和环境变化的复杂性,在OM源区和汇区稳定同位素的数量和质量有显著差异[7]。光谱指标能够通过端元混合分析区分陆源和水生OM[8],但主要基于大分子腐殖酸和富里酸来识别OM来源,并且生物地球化学变化会对来源混合OM的光学性质有着进一步影响[9]。而脂质生物标志物则针对单一分子群来跟踪OM来源,其不但可以区分外来源、本地源和人为输入,在某些情况下,甚至可以识别特定种类的生物体(例如细菌、植物、浮游生物)来源[10-12]。因此,脂质生物标记法对混合源的精准分辨而被广泛用于OM的溯源工作中[13-15]。正构烷烃通常用于区分陆源和水生OM[16],其降解速度与其他脂类相比缓慢,在沉积物中易积累[17]。甾醇被用于鉴定自然来源与人为粪便污染的分子标志物[18-19]。多环芳烃(PAHs)由于车辆排放,木材、草燃烧和石油燃烧等多重来源[20],通常被用作人类活动的标志[13]。而目前采用脂质生物标志物方法应用于河道型水库沉积物OM来源评估及其分布的研究却鲜有报道[21-22]。

大渡河梯级水电站是我国重要清洁能源基地之一,除了满足自身河段防洪要求外,还配合三峡水库对长江中下游发挥防洪作用[23]。梯级水电开发导致河岸生境破碎化程度的增加,并显著增加水力停留时间(HRT)[24],提升了对沉积物截留的效果[25]。因此,大渡河梯级水库是研究水库建立对河道水库沉积物OM的来源分布的理想场地。本研究利用GC-MS技术对瀑布沟水库(梯级下游控制水库)沉积物中OM分子标志物进行了定量分析,并根据来源将其分为自然标志物(高等植物、细菌和微藻、藻类)、人为标志物(包括成岩、热源和污水粪便)以及非特异性分子标志物,这种方法基于分子标志物的来源特异性,对有机化合物进行详尽量化和污染源划分。本研究的主要目的包括:(1)比较人为源和自然源输入对沉积物OM的贡献;(2)探究河道型水库沉积物OM的分布规律与来源特征;(3)揭示工业化和农业化对这个小型水文系统的影响。本研究结果能提高对典型河流上建设大坝过程中OM滞留情况的认识,为河流和大坝管理提供参考。

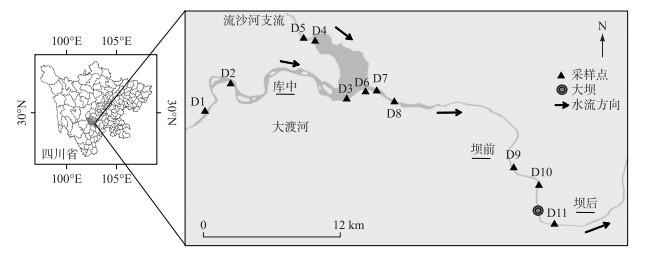

1 材料与方法 1.1 研究区域大渡河流经四川省中部和西部,是长江支流岷江的最大支流,全长约1062 km,流域面积约77440 km2,该流域主要由森林(37.0%)、草地(24.1%)、灌丛(15.7%)和其他土地利用类型组成,实行了大量水土保持措施以及封山育林等政策。大渡河梯级水电开发项目由3个控制性水库和22个电站级别组成,其中瀑布沟水电站是于2009年建成的第17级电站,属于下游控制性水库。库容高达5.39亿m3,水库区年均降雨量741.8 mm,平均温度22℃。瀑布沟水库建设改变了其原有的河道自然梯度和水流速度,在此范围内,汉源湖周边强烈的人为活动可能会影响水库的潜在人为OM。本研究以瀑布沟水库为研究区域,在库中、坝前及坝后选取采样点,如图 1所示,采样点具体信息见表 1。

|

图 1 采样点分布 Fig.1 Distribution of sampling sites |

| 表 1 采样点概况 Tab. 1 Basic information of sampling sites |

采样期间平均水深为749 m,库中、坝前和坝后平均流速为0.7、0.3和0.5 m/s。水体pH为8.0,呈弱碱性,CODCr、DO、NH3-N和TP的浓度分别为192.1~462.2、7.6~12.5、0.1~0.9和0.1~0.2 mg/L。

1.2 样品采集根据瀑布沟水库的水文地质特征和污染源分布情况,在流域内选取了11个具有代表性的采样点。采样时间为2019年12月,采样点在空间上分为3组:(1)D1~D5代表库中;(2)D6~D10代表坝前;(3)D11代表坝后。使用Peterson采样器(PBS-411)从0~5 cm深度收集表层沉积物。为确保沉积物的代表性,在每个地点采集一式三份样品,将3个样品混合以获得每个地点的沉积物样品,将样品用铝箔纸包裹、塑胶袋密封后,在4℃下保存。

1.3 测量和分析 1.3.1 沉积物粒径与有机质测定将采集的样品冷冻干燥,研磨并过筛(<2 mm)备用。表层沉积物粒径根据湖泊沉积物标准处理方法[26],约1 g样品用30%过氧化氢(1/1,v/v)处理,通过LS 230激光衍射颗粒分析仪(Microtrac S3500)测定颗粒尺寸,将沉积物粒度分为3类[27]:(1)黏土:<4 μm;(2)粉砂:4~63 μm;(3)粗砂:>63 μm。有机质(OM)采用烧失量法测定[28],将鲜样在烘箱(105℃)中烘至恒重后,称取烘干试样(0.5 g)平铺于瓷坩埚中,置于马弗炉550℃下煅烧4 h后的质量损失量定义为该样品中的有机质含量。

1.3.2 脂质生物标志物分析样品制备使用1~2 g冻干样品,采用加速溶剂萃取器(DionexTM ASETM 200),根据以下条件用二氯甲烷提取[29]:将有机萃取物浓缩至33 mL,在100℃和6×106 Pa条件下加热5 min,静置10 min,完成80%的冲洗和氮气吹扫200 s。总脂质组分通过在金属铜上还原除去元素硫。然后通过两步液相色谱法将总脂质提取物分馏成脂肪族、芳香族和极性化合物。高分子量的极性化合物被氧化铝保留,而碳氢化合物和低分子量极性分子被二氯甲烷洗脱下来,然后用甲醇/二氯甲烷(1/1,v/v)回收高分子量极性化合物。被洗脱下来的混合物用环己烷、环己烷/二氯甲烷(2/1,v/v)和甲醇/二氯甲烷(1/1,v/v)连续3次洗脱,并在硅胶柱(40~63 μm,默克)分馏成脂肪族、芳香族和低分子量极性化合物,将两个极性馏分合并,在N2条件下进行干燥,最后称重进行定量。

1.3.3 脂质生物标志物分析方法使用N, O-三甲基甲硅烷基(BSTFA)和三甲基氯硅烷(TMSC)(99/1,v/v)的混合物衍生化后分析极性馏分,将1 μL衍生样品注入气相色谱-质谱仪(QP2010SE GC-MS,Shimadzu)分析极性馏分,而对于脂肪族和芳香族馏分无需进一步处理直接进行分析。使用的进样器处于不分流模式,并保持310℃。在毛细管柱(SLB-5MS,默克,长度=60 m,直径=0.25 mm,膜厚度=0.25 μm)上进行色谱分离:70~130℃(保持1 min),速率为15℃/min,然后从130℃升温至300℃(保持15 min),速率为3℃/min。氦气流量保持在1 mL/min。色谱仪通过在280℃下加热的传输线连接到质谱仪,在全扫描模式下进行分析。在含有脂肪烃、芳香烃和极性化合物的溶液中加入内标,采用外标法进行有机化合物的定量[30]。

1.4 数据处理运用Excel 2003和Origin 2021对数据进行处理和图表绘制。

2 结果与讨论 2.1 沉积物粒径与OM分布水库作为河流中的“反应器”,阻碍了河水的流动,在降低河流流速的同时,还增加了河流水力停留时间。瀑布沟水库平均流速表现为库区(0.7 m/s)>坝后(0.5 m/s)>坝前(0.3 m/s)[24],这种差异性能显著影响沉积物粒径大小和OM含量的分布情况。研究区域以粉砂(47.2%±15.6%)和粗砂(39.7%±18.9%)为主(表 2)。库中中值粒径为(52.0±22.3) μm,坝前的中值粒径为(42.8±25.6) μm,坝后中值粒径为(92.9±12.0) μm,粒径空间分布表现为坝后>库中>坝前,坝后(D11)流速的增加,可能导致了细颗粒再悬浮和冲刷,在沉积物中留下更大的粗颗粒。黑河[31]和滦河[32]干流河道在空间上也表现出坝后粒径最大的趋势,表明梯级水库建设所产生的干扰作用是导致大坝下游沉积物粒径大幅度变化的重要原因。

| 表 2 水库表层沉积物OM组成与粒度参数 Tab. 2 Organic matter composition and particle size parameters of surface sediments |

一般来讲,沉积物中OM含量与颗粒大小呈正相关[33]。大颗粒将OM直接暴露于环境中,不能提供长期的物理保护[34],从而导致对OM吸附能力弱。而细颗粒的比表面积更大,为OM的长期物理或化学积累和储存过程创造了有利的条件[35]。此研究区域坝前沉积物OM(10.7%±4.8%)显著高于坝后(7.3%±0.9%)和库中(6.7%±1.8%),表明OM被水库明显地滞留在坝前[36-37],与我国三峡大坝[38]和法国克鲁萨河[39]的报告相一致。水坝的存在有效地阻碍了水动力学,导致坝前沉积了大量的细颗粒。与之相反,坝后较多细粒颗粒悬浮被水流冲走,而大颗粒对OM的吸附能力弱且对OM的保护能力较差[40],因此坝后OM含量较低。这与不同颗粒物对OM的吸附能力密切相关,说明水库的截留影响沉积物OM的积累。

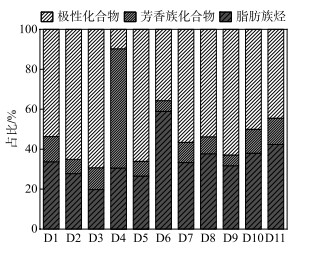

通过GC-MS定量的沉积物OM的脂质组分主要由极性化合物组成(图 2),平均占比为51.6%±17.1%,以空间平均比例来看,由库中(52.8%±24.8%)、坝前(51.8%±10.1%)到坝后(44.4%±8.1%)逐渐降低,然而脂肪族碳氢化合物的比例呈现出相反的趋势,即由库中(27.7%±5.2%)到坝前(39.9%±11.0%)再到坝后(42.4%±11.5%)逐渐升高。值得注意的是,除了D4外,芳烃的比例相对稳定,保持在13.9%±15.5%左右。此外,GC-MS量化的分子可以提供有关其来源的信息,并进行了明确的分类(表 3),这种分类可以区分沉积物中OM的不同输入并进行准确溯源。

|

图 2 可提取有机物的组成 Fig.2 The composition of extractable organic matter |

| 表 3 沉积物有机质中GC-MS测定的有机化合物分类* Tab. 3 Classification of organic compounds determined by GC-MS in organic matter |

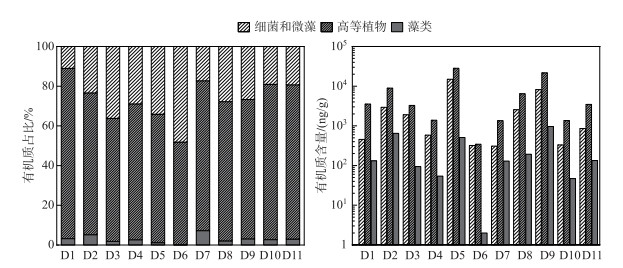

沉积物脂质组分中的自然标志物(表 3)可以分为细菌和微藻源、高等植物源和藻类源(图 3),其中,高等植物源标志物含量最多,比例为70.5%±9.1%(51.6%~85.8%);细菌和微藻标志物比例约为26.5%±10.3%(11.0%~48.1%);还含有少量藻类标志物,其比例为3.0%±1.9%(0.3%~7.2%)。然而,为了确定母源信息,通常需要根据脂质丰度的差异性指标追溯来源信息(附表Ⅰ)。

|

图 3 自然标志物来源解析 Fig.3 Source of natural markers |

CPI在数值上代表了原始生物链长度的保存程度[52],当CPI>5时,有奇偶数碳优势,这是来源于高等植物输入的特点[43];当CPI值接近于1.0时,没有奇数或偶数碳的偏好,表明来源于石油碳氢化合物[53-54]。在采样点沉积物中,CPI值介于1.9~9.5之间(表 4),平均值为5.5±2.4,强调了陆生高等植物的输入[55-56],而在D4、D6和D8点位表现出混合输入的特点。TAR和Paq分别用于评估OM陆生与水生输入以及区分陆地植物和水生植物的输入[57-58],TAR的相对比率在1.1~7.9之间,平均值为4.1±2.1,Paq介于0.1~0.2,均表现出以陆生植物输入为主。空间上看,来自高等植物分子标记的比例为坝后(77.7%±2.3%)>库中(70.5%±9.3%)>坝前(69.1%±10.4%)。标志分子主要是来自于nC24~nC34正构烷烃(奇数碳大于偶数碳)和高分子量的nC20~nC30正链烷醇(偶数比奇数的碳数占优势),这些化合物在植物腐烂后耐降解,通常可作为陆地高等植物向水体中输送的生物标志物[43]。此外,植物甾醇的出现也证明了高等植物的贡献,例如菜油甾醇和豆甾醇,它们是高等植物中的主要甾醇[56]。由表 1可知,由于当地封山育林政策,沿着大渡河,周边林地种植了大量的岷江柏木、云南松和云杉,成为了高等植物标记分子的重要来源[59]。

| 表 4 正构烷烃、芳香分子和类固醇的比率 Tab. 4 Ratio of n-alkanes, aromatic molecules and steroids |

细菌和微藻以及藻类均属于水中生物群来源,细菌和微藻主要是以短链正构烷烃(nC15~nC19)特征分子的出现[51],另外,菜子甾醇是水生初级生产者的标志物,这种分子是原生藻科以及几种硅藻(芽孢杆菌科)和甲藻(甲藻科)中的主要甾醇[60],沉积物样品还含有岩藻甾醇,支持浮游藻类的贡献。在空间上,细菌和微藻、藻类的分布特征变化表现为坝前(27.8%±12.2%、3.1%±2.6%)>库中(26.7%±10.1%、2.8%±1.5%)>坝后(19.3%±1.1%、3.0%±0.4%)。水库中营养物质的保留效率与HRT之间为正相关[61-62],低水力动力学条件使得细颗粒沉积,增加了沉积物的孔隙度。水库坝上游排放的大量工业和生活废水(表 1)有利于SRP和氨氮等生物可利用形式的营养盐在坝前滞留[24]。这些输入能促进细菌应激性快速响应,有利于微藻的生长,增加了脂质部分中水生生物群标志物,对湖泊初级生产力有着重要影响。

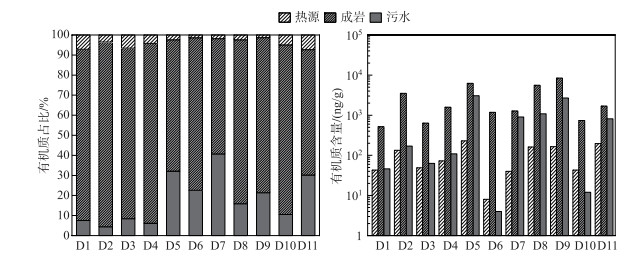

2.3 人为活动标志物来源随着城镇化进程的加快,许多工业园区兴起,进一步导致多环芳烃(PAHs)[63]和藿烷[64](表 3)等人为特征分子的出现。在人为来源标志物中,成岩标志物的占比最大,平均比例为77.9%±11.5%(最大值达到6262.1 ng/g)(图 4)。成岩标志物来自化石有机物的非热源性使用,广泛存在于润滑油[65]、润滑脂[15]和道路沥青[66]等石油副产品中。来自城市和工业废水[63]、大气沉降物[67]、城市化地区石油的渗滤和意外泄漏[65]等人为活动是它们在河流沉积物中吸附和积累的主要原因。成岩标志物在空间上表现为库中(83.5%±10.5%)>坝前(75.4%±10.6%)>坝后(62.5%±5.9%)。这主要与C12、C13和C14三种低分子量的正构烷烃有关,这些特征分子源自杂酚油,它们通常用于处理航海和户外部件(例如桥架),以防止腐烂[68]。在D6点位有着最高输入量(1180.8 ng/g),该采样点位于大渡河大桥东南侧,可能与附近的道路交通有关。藿烷是另一个重要成岩化合物,与芬什河和摩泽尔河汇合处的沉积物[13]类似,它通常来源于原油和石油产品(如煤油、汽油、柴油、润滑油和沥青),可以由原油和石油产品经下雨道路冲刷[16]以及碳氢化合物经大气干沉降和湿沉降[69]等方式进入河流沉积物。另外,成岩标记分子还有三环萜烷、降植烷、植烷和nC20~nC34正构烷烃(奇偶数相当)的出现,可能与近年来水库的修建以及工业的兴起等人为活动有关。

|

图 4 人类活动标志物来源解析 Fig.4 Source of human activity markers |

污水标志分子主要为粪甾醇(coprostanol),该分子来源于羊、牛、猪、猫和人类消化系统对胆固醇的降解[70]。一般来讲,R1的比值(附表Ⅰ)取决于产生它的动物,当该比值高于0.06则是人类粪便的特征[71]。该研究区域比值在0.06~0.66之间,显示出人类的特征。污水标志物表现为坝后(30.2%±4.6%)>坝前(22.2%±11.4%)>库中(11.7%±11.5%)(图 4)。根据实际的场地污染源调查,住宅生活污水处理设施覆盖率较不完善,绝大部分居民直接排放至周围的水渠流至河流中。并且当地农村地区大部分化粪池并没有进行集中处理[72],通常采用农家肥进行农业生产,下雨冲刷或者丰水期涨潮成为污水标志物的另一个输入途径[73-74]。

热源标志物的分布与生产活动密切相关,汉源城镇下游D6和D7点位(1.4%和1.8%)明显低于其他采样点(图 4)。热源标志物可以从几种燃烧过程中产生,如汽车尾气排放、木材燃烧、煤燃烧和煤焦油燃烧。通常使用相同分子质量同分异构体计算出来的比值来区分不同来源(附表Ⅰ),BaA/228的比值表明PAHs来源于热源和岩石输入的组合,但以热源输入为主[20]。Fl/(Fl+Py)的比值介于0.52~0.65之间,说明热源来源主要是草、木材、煤炭的燃烧[20],此外,燃烧源的分配还应由其他分子的比率来证实,如IP/(IP+Bghi),该比值介于0.38~0.48之间,偏向于液化石油燃料的燃烧[20]。进一步强调了研究区草、木材、煤燃烧以及液化石油燃料的组合贡献,说明居民仍然保持着较为传统的农业生产方式。为区分汽车尾气颗粒物的老化程度,测试了BaP/(BaP+BeP)的比值[75],除D9外,汽车尾气颗粒物均通过光解作用老化,表明道路交通是热源标志物的另一个重要来源方式。

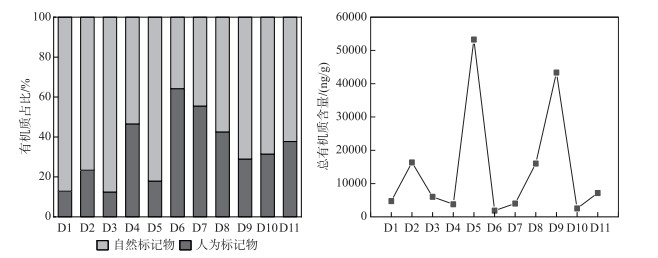

2.4 自然输入和人为输入的比较尽管在实际场地污染调查发现,瀑布沟水库存在工业、农业和人为活动的不规则排放,但脂质标志物却清晰地表明自然标志物占主导地位(图 5),与流涧河和北云河[15]、福尔摩沙咸水湖[49]和南海[50]沉积物的报告结果相类似。自然源占脂质定量分子的45.9%±13.9%(21.5%~67.3%),并主要来源于陆生高等植物。样品中测定的同源脂质化合物(正构烷烃、正链烷醇、正链烷酸和甾醇)表明,其分布与当地土地利用和河岸覆被类型有关。此外,还有生物群来源(细菌和微生物、藻类分别占自然标志分子的26.5%±10.3%、3.0%±1.9%),它们的空间分布情况与水库营养状况密切相关[76]。然而,本研究并没有评估微生物的丰富度和多样性,因为它们可能在湖泊养分循环中起着附加作用。据Abell等[77]的报道,细菌的群落组成与河口系统中OM的性质有关,它们可能会导致底栖营养通量的转变。

|

图 5 人为标志物和自然标志物的比较 Fig.5 Comparison of artificial and natural markers |

人为标志物占定量分子的24.6%±15.2%(8.7%~62.4%),其含量是自然标志物的1/2。库中污水标志物的相对贡献增多,热源的贡献减少。人为输入定量分子在整体上显示出坝前(33.0%±16.9%)大于库中(15.9%±10.3%),坝前靠近汉源城镇(D6和D7),人为活动显著(44.6%±25.1%)。这可能是因为D6和D7位于汉源县镇下游,处于汉源湖末端,伴随着水产养殖、污水排放等多源污染,加上大坝的截留作用,在水流速度较低的条件下限制了生物降解[78],同为河道型水库滃江[79]的研究中也有相似结果。而在整个采样区域,成岩分子的比例保持不变,石油原油和石油副产品(如燃料、润滑剂和沥青)是其成岩分子的主要来源。

研究区沉积物主要由粉砂(4~63 μm)组成,人为污染主要与成岩和污水输入而来的标记分子有关。当沉积物粒度分布以粉砂(4~63 μm)为中心时(表 2),人为标志物平均占量化分子的18.8%(9.9%~29.7%),成岩输入比污水输入高3.4倍。当粒度分布以粗砂(>63 μm)时,人为标志物代表了31.6%的量化分子,成岩输入比污水提高到4.5倍,然而,在芬什河和摩泽尔河汇合处的沉积物[13]以及普拉塔河沉积物[80]中,粒径差异在人为标记分子中主要是引起热解来源和成岩输入定量分子的变化,与本研究有所差异,可能与特定地貌和污染源组成变化有关。此外,本研究结果显示出自然标记物分子的定量与粒径无关。

瀑布沟水库沉积物脂质生物标志物的人为输入较自然输入低的原因可能是该流域森林覆被面积较多,有较高的陆生高等植物来源。同时在坝前的人为活动强度更大,而其他区域部分人口居住较为分散,影响范围相对于瀑布沟水库较小,因此流域的特征性显示出研究区域脂质生物标志物以自然输入为主导。

3 结论1) 本河流型水库研究范围内,沉积物OM平均含量呈现坝前(10.7%±4.8%)>坝后(7.3%±0.9%)>库尾(6.7%±1.8%)的趋势,OM被明显地滞留在坝前。这与坝前沉积了大量的细颗粒有关,说明水库的截留影响了沉积物OM的积累。

2) 自然来源标志物(45.9%±13.9%)是研究区沉积物脂类标志物的主要贡献者,CPI、TAR和Paq的相对比值显示OM主要来源于陆生高等植物。高等植物源占自然来源定量分子的70.5%±9.1%,其主要的标志化合物为nC24~nC34正构烷烃(奇数碳大于偶数碳占主导地位)和高分子量的nC20~nC30正链烷醇。

3) 坝前(靠近汉源城镇)的脂质标记物中人为输入占主导作用,与库中相比,人为输入标记分子的比例明显升高,并且污水输入的贡献率增多,这可能与该地住宅区生活污水处理设施覆盖率较低有关,其核心机制与水库滞留效应的耦合作用有关。

4 附录附表Ⅰ见电子版(DOI: 10.18307/2024.0126)。

| 附表Ⅰ 文献中用来区分天然有机质不同来源的比例限值 Appendix Ⅰ The proportion of OM used in the literature to distinguish different sources |

参考文献:

[1] Bray EE, Evans ED. Distribution of n-paraffins as a clue to recognition of source beds. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1961, 22(1): 2-15. DOI: 10.1016/0016-7037(61)90069-2.

[2] Ortiz JE, Moreno L, Torres T et al. A 220 ka palaeoenvironmental reconstruction of the Fuentillejo maar lake record (Central Spain) using biomarker analysis. Organic Geochemistry, 2013, 55: 85-97. DOI: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2012.11.012

[3] Sikes EL, Uhle ME, Nodder SD et al. Sources of organic matter in a coastal marine environment: Evidence from n-alkanes and their δ13C distributions in the Hauraki Gulf, New Zealand. Marine Chemistry, 2009, 113(3/4): 149-163. DOI: 10.1016/j.marchem.2008.12.003.

[4] Yunker MB, MacDonald RW, Vingarzan R et al. PAHs in the Fraser River Basin: A critical appraisal of PAH ratios as indicators of PAH source and composition. Organic Geochemistry, 2002, 33(4): 489-515. DOI: 10.1016/s0146-6380(02)00002-5.

[5] Jeanneau L, Faure P, Montarges-Pelletier E et al. Impact of a highly contaminated river on a more important hydrologic system: Changes in organic markers. Science of the Total Environment, 2006, 372(1): 183-192. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.09.021.

[6] Writer JH, Leenheer JA, Barber LB et al. Sewage contamination in the upper Mississippi River as measured by the fecal sterol, coprostanol. Water Research, 1995, 29(6): 1427-1436. DOI: 10.1016/0043-1354(94)00304-P.

| [1] |

Zeng H, Song LR, Yu ZG et al. Post-impoundment biomass and composition of phytoplankton in the Yangtze River. International Review of Hydrobiology, 2007, 92(3): 267-280. DOI:10.1002/iroh.200610893 |

| [2] |

Li YP, Hua L, Wang PF et al. Responses of hydrodynamical characteristics to climate conditions in a channel-type reservoir. J Lake Sci, 2013, 25(3): 317-23. [李一平, 滑磊, 王沛芳等. 河道型水库水动力特征与气候条件的响应关系. 湖泊科学, 2013, 25(3): 317-23. DOI:10.18307/2013.0301] |

| [3] |

贾晓斌. 新安江水库水环境演变的沉积物记录及碳埋藏研究[学位论文]. 上海: 上海大学, 2017.

|

| [4] |

He YY, Chen JY, Gao L et al. Spatial and temporal variations of sediment nutrients and relevant sources identification in Baipenzhu Reservoir, Guangdong Province. Ecology and Environmental Sciences, 2020, 29(7): 1419-1426. [何宜颖, 陈建耀, 高磊等. 惠州白盆珠水库沉积物营养元素时空变化特征及源解析. 生态环境学报, 2020, 29(7): 1419-1426.] |

| [5] |

Zhang XJ, Lu JP, Zhang SW et al. Characteristics and sources of organic matter in surface sediments of Dahekou Reservoir, China. Journal of Agro-Environment Science, 2019, 38(12): 2835-2843. [张晓晶, 卢俊平, 张圣微等. 大河口水库表层沉积物有机质特征及来源解析. 农业环境科学学报, 2019, 38(12): 2835-2843. DOI:10.11654/jaes.2019-0531] |

| [6] |

Lambert T, Teodoru CR, Nyoni FC et al. Along-stream transport and transformation of dissolved organic matter in a large tropical river. Biogeosciences, 2016, 13(9): 2727-2741. DOI:10.5194/bg-13-2727-2016 |

| [7] |

Li ZW, Wang SL, Nie XD et al. The application and potential non-conservatism of stable isotopes in organic matter source tracing. Science of the Total Environment, 2022, 838(Pt 1): 155946. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155946 |

| [8] |

Yang LY, Chang SW, Shin HS et al. Tracking the evolution of stream DOM source during storm events using end member mixing analysis based on DOM quality. Journal of Hydrology, 2015, 523: 333-341. DOI:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2015.01.074 |

| [9] |

Zhou YQ, Shi K, Zhang YL et al. Fluorescence peak integration ratio IC ∶IT as a new potential indicator tracing the compositional changes in chromophoric dissolved organic matter. Science of the Total Environment, 2017, 574: 1588-1598. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.08.196 |

| [10] |

Parrish CC, Abrajano TA, Budge SM et al. Lipid and phenolic biomarkers in marine ecosystems: Analysis and applications. The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2005: 193-223. DOI: 10.1007/10683826_8.

|

| [11] |

Bergé JP, Barnathan G. Fatty acids from lipids of marine organisms: Molecular biodiversity, roles as biomarkers, biologically active compounds, and economical aspects. Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology, 2005, 96: 49-125. DOI:10.1007/b135782 |

| [12] |

Li ZW, Sun YZ, Nie XD. Biomarkers as a soil organic carbon tracer of sediment: Recent advances and challenges. Earth-Science Reviews, 2020, 208: 103277. DOI:10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103277 |

| [13] |

Jeanneau L, Faure P, Montarges-Pelletier E et al. Impact of a highly contaminated river on a more important hydrologic system: Changes in organic markers. Science of the Total Environment, 2006, 372(1): 183-192. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.09.021 |

| [14] |

Kaal J, Cortizas AM, Biester H. Downstream changes in molecular composition of DOM along a headwater stream in the Harz Mountains (Central Germany) as determined by FTIR, Pyrolysis-GC-MS and THM-GC-MS. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis, 2017, 126: 50-61. DOI:10.1016/j.jaap.2017.06.025 |

| [15] |

Li ZH, Zhang WQ, Shan BQ. Effects of organic matter on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in riverine sediments affected by human activities. Science of the Total Environment, 2022, 815. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152570 |

| [16] |

Wang ZD, Stout SA, Fingas M. Forensic fingerprinting of biomarkers for oil spill characterization and source identification. Environmental Forensics, 2006, 7(2): 105-146. DOI:10.1080/15275920600667104 |

| [17] |

Ficken KJ, Li B, Swain DL et al. An n-alkane proxy for the sedimentary input of submerged/floating freshwater aquatic macrophytes. Organic Geochemistry, 2000, 31(7/8): 745-749. DOI:10.1016/S0146-6380(00)00081-4 |

| [18] |

Volkman JK, Barrett SM, Blackburn SI et al. Microalgal biomarkers: A review of recent research developments. Organic Geochemistry, 1998, 29(5/6/7): 1163-1179. DOI:10.1016/S0146-6380(98)00062-X |

| [19] |

Ding L, Xing L, Zhao MX. Applications of biomarkers for reconstructing phytoplankton productivity and community structure changes. Advances in Earth Science, 2010, 25(9): 981-989. [丁玲, 邢磊, 赵美训. 生物标志物重建浮游植物生产力及群落结构研究进展. 地球科学进展, 2010, 25(9): 981-989.] |

| [20] |

Yunker MB, MacDonald RW, Vingarzan R et al. PAHs in the Fraser River Basin: A critical appraisal of PAH ratios as indicators of PAH source and composition. Organic Geochemistry, 2002, 33(4): 489-515. DOI:10.1016/s0146-6380(02)00002-5 |

| [21] |

Dachs J, Bayona JM, Fillaux J et al. Evaluation of anthropogenic and biogenic inputs into the western Mediterranean using molecular markers. Marine Chemistry, 1999, 65(3/4): 195-210. DOI:10.1016/S0304-4203(99)00002-X |

| [22] |

Derrien M, Cabrera FA, Tavera NLV et al. Sources and distribution of organic matter along the Ring of Cenotes, Yucatan, Mexico: Sterol markers and statistical approaches. Science of the Total Environment, 2015, 511: 223-229. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.12.053 |

| [23] |

Yan JJ. Study on flood control and water storage of main stream reservoirs on Dadu River. Sichuan Water Power, 2020, 39(4): 139-142. [严锦江. 大渡河干流水库群防洪与蓄水研究. 四川水力发电, 2020, 39(4): 139-142.] |

| [24] |

Yin YP, Zhang W, Tang JY et al. Impact of river dams on phosphorus migration: A case of the Pubugou Reservoir on the Dadu River in China. Science of the Total Environment, 2022, 809: 151092. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151092 |

| [25] |

郑声安, 陈五一, 叶发明. 大渡河瀑布沟水电站大坝防渗设计. 中国水力发电论文集. 2008: 327-330.

|

| [26] |

范成新. 湖泊沉积物调查规范. 北京: 科学出版社, 2018.

|

| [27] |

Liang Z, Liu ZM, Zhen SM et al. Phosphorus speciation and effects of environmental factors on release of phosphorus from sediments obtained from Taihu Lake, Tien Lake, and East Lake. Toxicological & Environmental Chemistry, 2015, 97(3/4): 335-348. DOI:10.1080/02772248.2015.1050186 |

| [28] |

Zheng PR, Li CH, Ye C et al. Distribution characteristics and release contribution of different phosphorus forms in sediments of Jingpo Lake. China Environmental Science, 2021, 41(2): 883-890. [郑培儒, 李春华, 叶春等. 镜泊湖沉积物各形态磷分布特征及释放贡献. 中国环境科学, 2021, 41(2): 883-890.] |

| [29] |

Derrien M, Jardé E, Gruau G et al. Extreme variability of steroid profiles in cow feces and pig slurries at the regional scale: Implications for the use of steroids to specify fecal pollution sources in waters. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2011, 59(13): 7294-7302. DOI:10.1021/jf201040v |

| [30] |

Oros DR, Mazurek MA, Baham JE et al. Organic tracers from wild fire residues in soils and rain/river wash-out. Water, Air, and Soil Pollution, 2002, 137(1): 203-233. DOI:10.1023/A:1015557301467 |

| [31] |

Wang Y, Lian YT, Feng Q et al. Effects of dam interception on the spatial distribution of sediment granularities in Heihe River. J Lake Sci, 2019, 31(5): 1459-1467. [王昱, 连运涛, 冯起等. 筑坝拦截对黑河河道沉积物粒度空间分布的影响. 湖泊科学, 2019, 31(5): 1459-1467. DOI:10.18307/2019.0505] |

| [32] |

Liu JL, Bao K, Li Y et al. Spatial distribution characteristics in grain size of river surface sediments under the influence of reservoirs in the Luanhe River Basin. Journal of Agro-Environment Science, 2015, 34(5): 955-963. [刘静玲, 包坤, 李毅等. 滦河流域水库对河流表层沉积物粒度空间分布影响的研究. 农业环境科学学报, 2015, 34(5): 955-963. DOI:10.11654/jaes.2015.05.019] |

| [33] |

Galy V, France-Lanord C, Lartiges B. Loading and fate of particulate organic carbon from the Himalaya to the Ganga-Brahmaputra delta. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2008, 72(7): 1767-1787. DOI:10.1016/j.gca.2008.01.027 |

| [34] |

Liao JD, Boutton TW, Jastrow JD. Storage and dynamics of carbon and nitrogen in soil physical fractions following woody plant invasion of grassland. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2006, 38(11): 3184-3196. DOI:10.1016/j.soilbio.2006.04.003 |

| [35] |

Zhao C, Dong SK, Liu SL et al. Preliminary study on the effect of cascade dams on organic matter sources of sediments in the middle Lancang-Mekong River. Journal of Soils and Sediments, 2018, 18(1): 297-308. DOI:10.1007/s11368-017-1790-5 |

| [36] |

Ma QQ, Wei X, Wu Y et al. Composition and distribution of organic matter in the surface sediments of the Changjiang River in Post-Three Gorges Dam period. China Environmental Science, 2015, 35(8): 2485-2493. [马倩倩, 魏星, 吴莹等. 三峡大坝建成后长江河流表层沉积物中有机物组成与分布特征. 中国环境科学, 2015, 35(8): 2485-2493.] |

| [37] |

Wu LS, Tong HJ, Liu G et al. Study on the characteristics of organic matter pollution in lake reservoir water source area—Taking H reservoir in southern Sichuan as an example. Sichuan Environment, 2022, 41(4): 140-151. [邬丽姗, 佟洪金, 刘国等. 湖库型水源地有机质污染特征研究——以川南地区H水库为例. 四川环境, 2022, 41(4): 140-151.] |

| [38] |

Rapin A, Rabiet M, Mourier B et al. Sedimentary phosphorus accumulation and distribution in the continuum of three cascade dams (Creuse River, France). Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 2020, 27(6): 6526-6539. DOI:10.1007/s11356-019-07184-6 |

| [39] |

Xu FC, Chen LM, Xu YF et al. Impact of the Three Gorges Dam on the quality of riverine dissolved organic matter. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2020, 104(4): 538-544. DOI:10.1007/s00128-020-02791-3 |

| [40] |

Zhao C, Liu SL, Dong SK et al. Spatial and seasonal dynamics of organic carbon in physically fractioned sediments associated with dam construction in the middle Lancang-Mekong River. Journal of Soils and Sediments, 2015, 15(11): 2323-2333. DOI:10.1007/s11368-015-1191-6 |

| [41] |

Cook P, Revill AT, Clementson LA et al. Carbon and nitrogen cycling on intertidal mudflats of a temperate Australian Estuary. Ⅲ. Sources of organic matter. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 2004, 280: 55-72. DOI:10.3354/meps280055 |

| [42] |

Derrien M, Yang LY, Hur J. Lipid biomarkers and spectroscopic indices for identifying organic matter sources in aquatic environments: A review. Water Research, 2017, 112: 58-71. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2017.01.023 |

| [43] |

Eglinton G, Hamilton RJ. Leaf Epicuticular Waxes: The waxy outer surfaces of most plants display a wide diversity of fine structure and chemical constituents. Science, 1967, 156(3780): 1322-1335. DOI:10.1126/science.156.3780.1322 |

| [44] |

Killops S. Introduction to organic geochemistry, 2nd edn (paperback). Geofluids, 2005, 5(3): 236-237. DOI:10.1111/j.1468-8123.2005.00113.x |

| [45] |

Meziane T, Tsuchiya M. Fatty acids as tracers of organic matter in the sediment and food web of a mangrove/intertidal flat ecosystem, Okinawa, Japan. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 2000, 200: 49-57. DOI:10.3354/meps200049 |

| [46] |

Rommerskirchen F, Plader A, Eglinton G et al. Chemotaxonomic significance of distribution and stable carbon isotopic composition of long-chain alkanes and alkan-1-ols in C4 grass waxes. Organic Geochemistry, 2006, 37(10): 1303-1332. DOI:10.1016/j.orggeochem.2005.12.013 |

| [47] |

Jaffé R, Mead R, Hernandez ME et al. Origin and transport of sedimentary organic matter in two subtropical estuaries: A comparative, biomarker-based study. Organic Geochemistry, 2001, 32(4): 507-526. DOI:10.1016/S0146-6380(00)00192-3 |

| [48] |

Santos SAO, Vilela C, Freire CSR et al. Chlorophyta and Rhodophyta macroalgae: A source of health promoting phytochemicals. Food Chemistry, 2015, 183: 122-128. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.03.006 |

| [49] |

Jardé E, Jeanneau L, Harrault L et al. Application of a microbial source tracking based on bacterial and chemical markers in headwater and coastal catchments. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 610/611: 55-63. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.07.235 |

| [50] |

The biomarker guide: Interpreting molecular fossils in petroleum and ancient sediments. Choice Reviews Online, 1993, 30(5): 30-2690. DOI: 10.5860/choice.30-2690.

|

| [51] |

Pisani O, Oros DR, Oyo-Ita OE et al. Biomarkers in surface sediments from the Cross River and estuary system, SE Nigeria: Assessment of organic matter sources of natural and anthropogenic origins. Applied Geochemistry, 2013, 31: 239-250. DOI:10.1016/j.apgeochem.2013.01.010 |

| [52] |

Meyers PA, Ishiwatari R. Lacustrine organic geochemistry—An overview of indicators of organic matter sources and diagenesis in lake sediments. Organic Geochemistry, 1993, 20(7): 867-900. DOI:10.1016/0146-6380(93)90100-P |

| [53] |

Liang ZB, Sun YC, Li JH et al. Sources and variation characteristics of dissolved lipid biomarkers in a typical Karst underground river. Environmental Science, 2016, 37(5): 1814-1822. [梁作兵, 孙玉川, 李建鸿等. 典型岩溶区地下河中溶解态脂类生物标志物来源解析及其变化特征. 环境科学, 2016, 37(5): 1814-1822. DOI:10.13227/j.hjkx.2016.05.027] |

| [54] |

Bray EE, Evans ED. Distribution of n-paraffins as a clue to recognition of source beds. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1961, 22(1): 2-15. DOI:10.1016/0016-7037(61)90069-2 |

| [55] |

Colombo JC, Cappelletti N, Lasci J et al. Sources, vertical fluxes, and accumulation of aliphatic hydrocarbons in coastal sediments of the Río de la Plata Estuary, Argentina. Environmental Science & Technology, 2005, 39(21): 8227-8234. DOI:10.1021/es051205g |

| [56] |

Jeanneau L, Faure P, Montarges-Pelletier E. Quantitative multimolecular marker approach to investigate the spatial variability of the transfer of pollution from the Fensch River to the Moselle River (France). Science of the Total Environment, 2008, 389(2/3): 503-513. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.09.023 |

| [57] |

Ortiz JE, Moreno L, Torres T et al. A 220 ka palaeoenvironmental reconstruction of the Fuentillejo maar lake record (Central Spain) using biomarker analysis. Organic Geochemistry, 2013, 55: 85-97. DOI:10.1016/j.orggeochem.2012.11.012 |

| [58] |

Sikes EL, Uhle ME, Nodder SD et al. Sources of organic matter in a coastal marine environment: Evidence from n-alkanes and their δ13C distributions in the Hauraki Gulf, New Zealand. Marine Chemistry, 2009, 113(3/4): 149-163. DOI:10.1016/j.marchem.2008.12.003 |

| [59] |

Phillips KM, Ruggio DM, Ashraf-Khorassani M. Phytosterol composition of nuts and seeds commonly consumed in the United States. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2005, 53(24): 9436-9445. DOI:10.1021/jf051505h |

| [60] |

Mudge SM, Bebianno MJA, East JA et al. Sterols in the ria formosa lagoon, Portugal. Water Research, 1999, 33(4): 1038-1048. DOI:10.1016/S0043-1354(98)00283-8 |

| [61] |

Kõiv T, Nõges T, Laas A. Phosphorus retention as a function of external loading, hydraulic turnover time, area and relative depth in 54 lakes and reservoirs. Hydrobiologia, 2011, 660(1): 105-115. DOI:10.1007/s10750-010-0411-8 |

| [62] |

Maavara T, Chen QW, Van Meter K et al. River Dam impacts on biogeochemical cycling. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 2020, 1(2): 103-116. DOI:10.1038/s43017-019-0019-0 |

| [63] |

Tao S, Cui YH, Xu FL et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in agricultural soil and vegetables from Tianjin. Science of the Total Environment, 2004, 320(1): 11-24. DOI:10.1016/S0048-9697(03)00453-4 |

| [64] |

Zeng SY, Zeng L, Dong X et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in river sediments from the western and southern catchments of the Bohai Sea, China: Toxicity assessment and source identification. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 2013, 185(5): 4291-4303. DOI:10.1007/s10661-012-2869-5 |

| [65] |

Patience RL. Fossil fuel biomarkers, applications and spectra. Earth-Science Reviews, 1986, 23(3): 230. DOI:10.1016/0012-8252(86)90024-3 |

| [66] |

Faure P, Landais P, Schlepp L et al. Evidence for diffuse contamination of river sediments by road asphalt particles. Environmental Science & Technology, 2000, 34(7): 1174-1181. DOI:10.1021/es9909733 |

| [67] |

Zhang Y, Guo CS, Xu J et al. Potential source contributions and risk assessment of PAHs in sediments from Taihu Lake, China: Comparison of three receptor models. Water Research, 2012, 46(9): 3065-3073. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2012.03.006 |

| [68] |

Nishi I, Yoshitomi T, Nakano F et al. Development of a safer and improved analytical method for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in creosote products. Journal of Chromatography A, 2023, 1698: 464007. DOI:10.1016/j.chroma.2023.464007 |

| [69] |

Gogou A, Bouloubassi I, Stephanou EG. Marine organic geochemistry of the Eastern Mediterranean: 1. Aliphatic and polyaromatic hydrocarbons in Cretan Sea surficial sediments. Marine Chemistry, 2000, 68(4): 265-282. DOI:10.1016/S0304-4203(99)00082-1 |

| [70] |

Leeming R, Ball A, Ashbolt N et al. Using faecal sterols from humans and animals to distinguish faecal pollution in receiving waters. Water Research, 1996, 30(12): 2893-2900. DOI:10.1016/S0043-1354(96)00011-5 |

| [71] |

Writer JH, Leenheer JA, Barber LB et al. Sewage contamination in the upper Mississippi River as measured by the fecal sterol, coprostanol. Water Research, 1995, 29(6): 1427-1436. DOI:10.1016/0043-1354(94)00304-P |

| [72] |

Luo F, Pan A, Zhang H. Investigation and control of rural environmental pollution: Take Hanyuan County in Sichuan as an example. Journal of Yunnan Agricultural University: Social Science, 2021, 15(4): 143-147. [罗芳, 潘安, 张寒. 农村环境污染现状调查与污染治理——以四川省汉源县为例. 云南农业大学学报: 社会科学, 2021, 15(4): 143-147.] |

| [73] |

Cao Q, Wang M, Qin L. Analysis of pollution load and water environment capacity of Jinshahe Reservoir. Journal of Hubei University: Natural Science Edition, 2023, 45(1): 47-52. [曹倩, 王敏, 秦柳. 金沙河水库污染负荷与水环境容量分析. 湖北大学学报: 自然科学版, 2023, 45(1): 47-52.] |

| [74] |

Hu LM, Guo ZG, Feng JL et al. Distributions and sources of bulk organic matter and aliphatic hydrocarbons in surface sediments of the Bohai Sea, China. Marine Chemistry, 2009, 113(3/4): 197-211. DOI:10.1016/j.marchem.2009.02.001 |

| [75] |

Dickhut RM, Canuel EA, Gustafson KE et al. Automotive sources of carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons associated with particulate matter in the Chesapeake Bay region. Environmental Science & Technology, 2000, 34(21): 4635-4640. DOI:10.1021/es000971e |

| [76] |

Jiang B, Zheng HL, Huang GQ et al. Characterization and distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon in sediments of Haihe River, Tianjin, China. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2007, 19(3): 306-311. DOI:10.1016/S1001-0742(07)60050-3 |

| [77] |

Abell G, Ross DJ, Keane JP et al. Nitrifying and denitrifying microbial communities and their relationship to nutrient fluxes and sediment geochemistry in the Derwent Estuary, Tasmania. Aquatic Microbial Ecology, 2013, 70(1): 63-75. DOI:10.3354/ame01642 |

| [78] |

Jeanneau L, Faure P, Montarges-Pelletier E. Evolution of the source apportionment of the lipidic fraction from sediments along the Fensch River, France: A multimolecular approach. Science of the Total Environment, 2008, 398(1/2/3): 96-106. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.02.028 |

| [79] |

Zeng HP, Gao L, Chen JY et al. Historical reconstruction and source identification of sediment nutrient elements in the Changhu Reservoir, Wengjiang River. China Environmental Science, 2017, 37(10): 3910-3918. [曾红平, 高磊, 陈建耀等. 滃江长湖水库沉积物营养元素沉积历史重构及源解析. 中国环境科学, 2017, 37(10): 3910-3918.] |

| [80] |

Colombo JC, Barreda A, Bilos C et al. Oil spill in the Rio de la Plata estuary, Argentina: 2-hydrocarbon disappearance rates in sediments and soils. Environmental Pollution, 2005, 134(2): 267-276. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2004.07.028 |

2024, Vol. 36

2024, Vol. 36